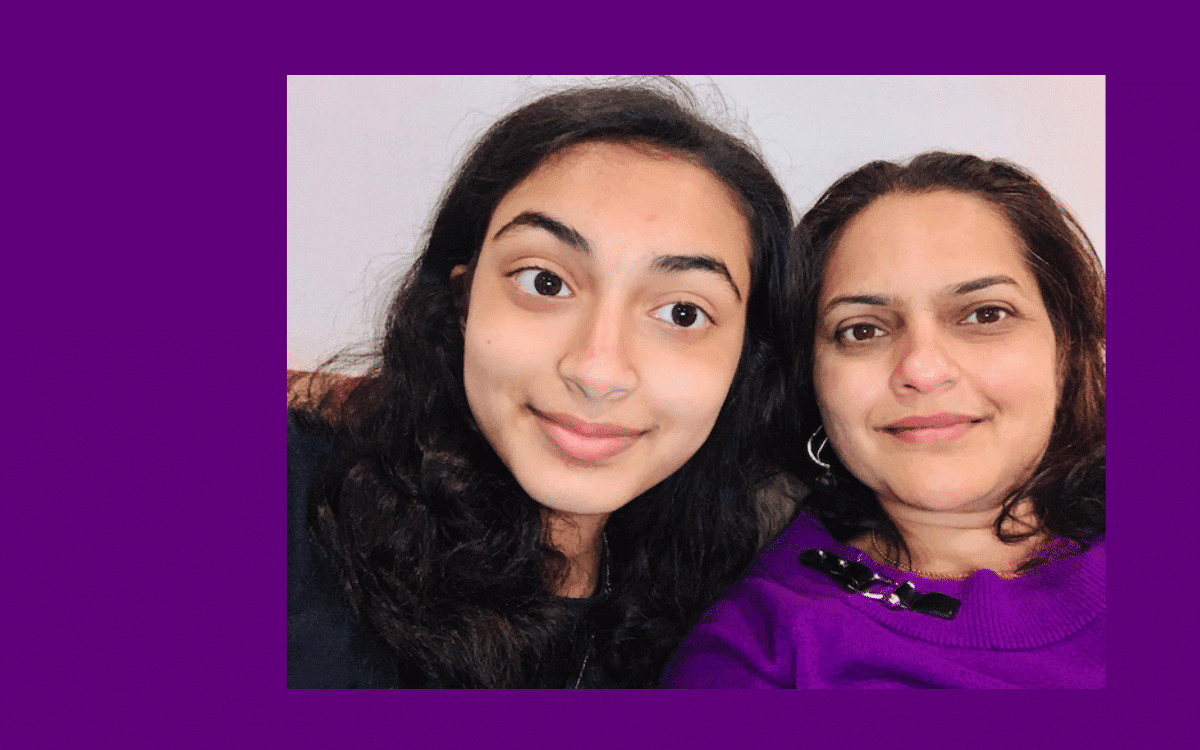

(Photo courtesy of Shreya Prabhu)

(Photo courtesy of Shreya Prabhu)

When you imagine feminism, you might think about Katherine Johnson of “Hidden Figures” or Ruth Bader Ginsburg from “On The Basis Of Sex,” but what about the women in our everyday lives? When I look at the women on my mom’s side — specifically, my hodi-mamama (great grandmother), my mamama (grandmother) and my mother, they are a trifecta of strength. Even though they were raised in periods of history where women were told to be silent and pretty, they each emulate a bold take on feminism, inspiring me to be persistent in fighting for what’s right in my school and community. Because of their positive influence, I wrote an essay about racism in my school and how it has affected me. This led me and a friend to organize “Stand Up To Racism Day” at our school, to address the recent issues of police brutality and Asian-American hate crimes.

I believe it’s important to shed light on the older women who have paved the path for me. So, let’s start by recognizing my great-grandmother.

I admire how radiant my hodi-mamama looks in this hand-crafted saree, adorned with delicate stitches of silk. She was born in 1928, the youngest of seven children and adopted by her older sister. My hodi-mamama was a remarkable student who ranked first in her 10th grade exams, but much to her disappointment, her ambitious nature was put on hold to get married at 19. Although she may have looked petite, her words were opinionated and blunt. The filter between her thoughts and words was minimal, something that set her apart from the typical social norm of women in India in the mid-1900s.

My hodi-mamama was a role model for women in her time by fervently advocating for women’s rights. She was a passionate social worker who pushed for my mamama to get a good education and complete college. My favorite quote of hers was, “I was born alone and I will die alone,” when asked why she was at a party without her husband. This is a simple statement, but it says a great deal about her independent character. In fact, she lived in an apartment by herself even after her husband passed away, an uncommon lifestyle for women of her generation. Though she died in 2001, years before I was born, her vibrant spirit lives on today.

My mamama is a less intense version of my hodi-mamama. She graces the room with her quiet confidence, is diplomatic and insightful. Don’t mistake her for a pushover though; she gets her thoughts across just as clearly as my hodi-mamama did. My mamama doesn’t gloat when success comes her way, making her even more likeable and sophisticated. A graduate of Wilson College in Mumbai (a top 25 school in India), she has been a stellar student her entire life. She graduated with a Bachelor’s in Microbiology and a Master’s in Linguistics, Public Administration, Mass Communications and English Literature. On top of that, she also received a PhD in Social Work from Zoroastrian College while taking care of her two small kids, my mother and uncle.

Her accomplishments didn’t stop there. She presented at the United Nations twice — once in 2018, and again in 2021 about access to girls’ education in rural India. She was willing to put herself out there and speak about a hard topic, further representing her intrepid nature. She recently told me, “Being feminist … means you have to be bold, you have to know what you want and express yourself properly, without being aggressive.” These three checkpoints are exactly what she has performed in her life. Throughout the course of her own career as a writer, (where she has published four books and six e-books) she has been a great mother without compromising her career path.

My mother is a combination of the two. While she’s known to speak her mind, she’s still easygoing. You can find her engrossed in a classic book, eyes swiveling from page to page for hours. Nature is her solace, where she can sit for hours at a time, with the company of wild animals and plants. One of her most distinctive qualities is that she never judges those around her. Her opinions of people aren’t muddled by their words or their actions, and she constantly converses with people, coming from an angle of trust. Although she grew up in a more representative time for women, she is no stranger to misogyny.

When she was in engineering school, she remembers a male professor saying, “You are wasting a precious spot in our college. You will get married and stop working anyways.” Though the professor’s words stung, my mother persisted and continued to sparkle in her class of a meager eight girls and 72 boys. She made it crystal clear that the fight for feminism has not yet been won yet when she explained, “I think feminism is a very misunderstood word … women have to have equitability — not just equality. Feminism is about making sure your voice is heard.” That said, my mother is a proponent of women having equal pay and say in the corporate world, where a scant 6% of women are CEOs. She ardently advocates for working moms in her own generation, from decreasing their evening workload to having later start times to morning meetings.

I like to think that I embody some qualities of all the women in my family: my hodi-mamama’s courage, my mamama’s confidence and my mother’s honesty. To me, feminism means that everyone’s voice is heard, respected and acted on; and I thank each of them for helping shape this definition.